In the past few years, I’ve seen several anime that seek to capture the spirit of rural living, to varied success. No-Rin was fairly educational but its appeal was more in the characters and their hijinks. It was a pretty generic show that had the added bonus of farm-related punchlines. A big appeal of Non Non Biyori was the focus on rural living, but it was more for the pretty backgrounds than anything and it seemed to be a “how do we entertain ourselves in the sticks” show than what I was looking for.

I bring those up because they managed to get things half right. No-Rin knew what it was talking about and many viewers of Non Non Biyori apparently took something from the setting, but as someone who’s spent his entire life in a rural area they just sort of lacked something. Silver Spoon (Gin no Saji), on the other hand, is quite possibly the best portrayal of rural, agricultural life I’ve seen not only in anime, but in anything I’ve watched.

Silver Spoon is written by Hiromu Arakawa of Fullmetal Alchemist fame. That’s right: the woman who wrote the incredibly successful fantasy manga is also responsible for a slice-of-life agricultural comedy. This shouldn’t be too surprising for those who have seen her end-of-volume illustrations for FMA. She grew up in rural Hokkaido (one of the most agricultural areas of Japan), and her connection to farm life comes across in several ways. She draws herself as a bespectacled Holstein, and when asked why her character design isn’t as thin as the norm, she says she doesn’t want to give the impression that her characters aren’t eating well (“Men should be buff! Women should be vavoom!”). So while a farm-based slice-of-life sounds like it couldn’t be more different from Fullmetal Alchemist, it also seems like a natural choice for Arakawa as a person.

During the summer of 2014, I spent four weeks working on a farm in Hokkaido through Mennonite Mission Network. It was a fantastic experience, and I’m seriously considering going back at some point. Hokkaido is easily the largest Japanese prefecture, so I can’t pretend to be able to speak for it as a whole, but from what I saw (which was around the Sapporo area), it’s a beautiful place. I live in South Dakota, where everything is flat and laid out in neat little square miles (assuming we’re talking about East River SD. West River doesn’t count). It’s a patchwork quilt of fields stitched together by gravel roads and barbed wire, broken up by the occasional farmyard or town. We even have one or two things that kind of count as cities, by which I mean they’re larger towns that have a Wal-Mart. It’s a place that’s very flat, very spread-out, and is consequently naturally inclined towards agriculture.

Hokkaido, on the other hand (or at least where I was), packs everything together in an odd blend of urban and rural. It’s a series of mountains and valleys, where every valley is filled with fields or towns. Almost all the roads I saw were paved, and even if they didn’t get much traffic, it gave the sense that even the rural areas were very lived in. There was a small ski resort right by the property I was working, close enough that our group considered climbing it one morning (it was a bit further and higher than it looked so we didn’t, but we did get to drive up there and view the farm from above). It’s a “best of both worlds” type of place: it’s isolated, but close enough to society that it doesn’t feel isolating. It’s been industrialized, but because of all the mountains, it still feels like it’s surrounded by nature.

I feel like I’m not describing Hokkaido particularly well. Fortunately, I don’t need to, because everything I’m trying to say about it is captured wonderfully by the first few moments of Silver Spoon, when the protagonist Hachiken finds himself in a snowy field with no cell reception.

These images are the second scene in the anime (directly following the OP), but are the very first images presented in the manga, and these initial moments tell you almost everything you need to know about the setting of Silver Spoon. The blue skies establish that Hachiken is away from the pollution of cities. The fox carrying the small rodent through the trees helps establish the feeling of wilderness. This isn’t a place with a city’s comforts and conveniences. This is a place where Hachiken is going to be working for his meals. The lack of cell reception tells us how isolated Hachiken is. Not only is he away from many of the comforts of the city, he’s going to have a much smaller network of people to interact with. He’ll be learning to work with people around him rather than choosing people around him to associate with. His friends will be ones of shared experiences rather than shared interests. The calf, tags in its ears, treats him with affection rather than fear. This shows that, despite this wilderness, there is still some sense of domestication of the area. Human hands have been here. And the final shot provides an image of the physical setting, as well as providing a bit of scope to show just how lonely it seems. Hachiken is nowhere near the rest of civilization. He’s in a wide-open field, with nothing around but trees, mountains, and melting snow. We instantly get a sense of how out of his element he is, as well as seeing the natural beauty of the area and getting a good sense of the time of year this is taking place. All of that in just 25 seconds of anime or 3 pages of manga.

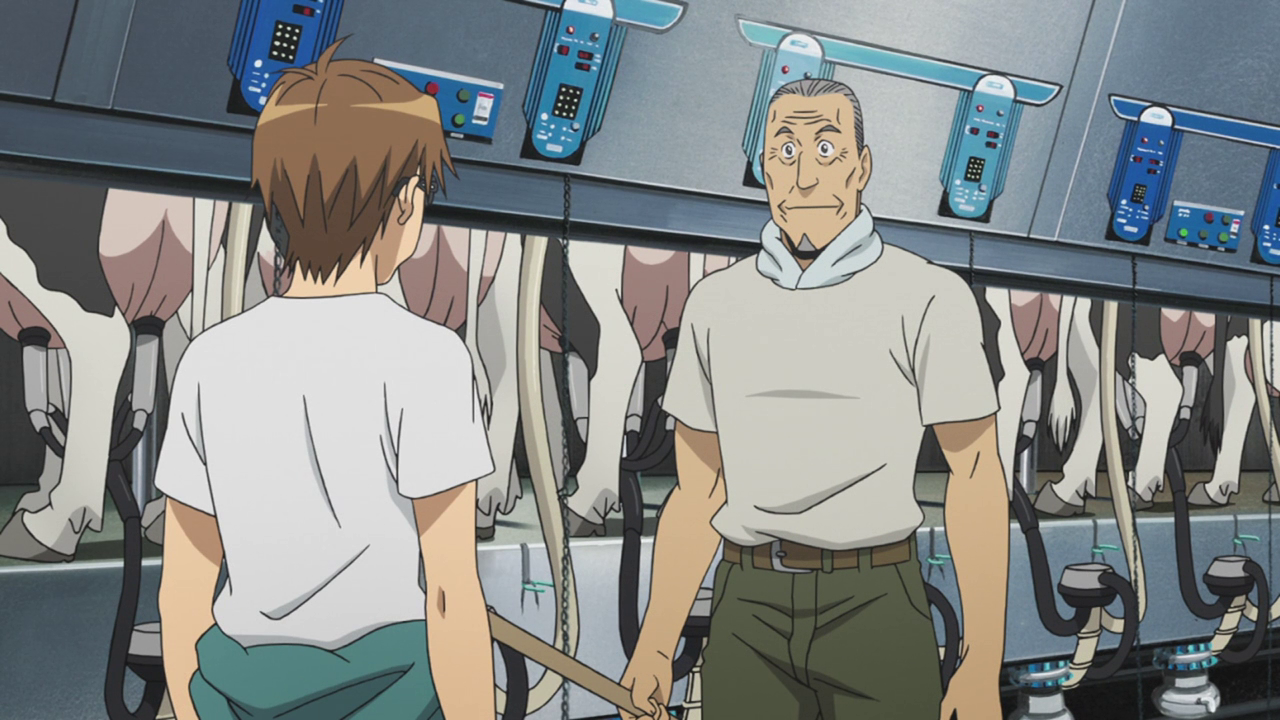

Taking care of a farm often means waking up at 5 AM. It’s when light returns to the world, or at least something resembling light. I never grew up on a dairy farm so I can’t be positive I have all my facts right, but I’m fairly certain that milking happens on a routine schedule and is really important for the cows’ health. Even discounting milking, animals need to be fed, and sometimes there’s no time to do it later. I have vivid memories of my senior year of high school, when my grandpa was nearing the end of his battle with cancer and couldn’t take care of the farm on his own anymore, and it fell to me to help out. In order to get everything done before school, I had to wake up early, drive the roughly six miles to where he lived, and give grain and hay to his cattle. This happened to be during the winter. Keep in mind that I live in South Dakota, where the winters can get pretty harsh. Sometimes there was snow. Even when there wasn’t, it was usually below freezing outside. Either way, this scene, with Hachiken’s team waking up early to trudge through the gray, foggy twilight? It’s a scene I’m well-acquainted with.

The setting of Silver Spoon is seen through more than just the environment. It’s embodied in the characters. A large part of Hachiken’s reason for joining this school in the first place was because he wanted to excel academically compared to what he saw as backwards country rubes. What he failed to realize is that, while farmers may be simple people (though “down-to-earth” is maybe a better phrase) and aren’t academics by any means, they have some very in-depth specific scientific knowledge. Animal science, plant science, meteorology, accounting, and often a lot of mechanical and electrical knowledge are required in order to run a farm. If you want your animals to thrive, you’re going to have to know how to keep them healthy. If you want your plants to thrive, you need to understand pH balances and crop rotation. If you’re using large machinery in order to get work done, you’re going to need to know how to fix it. And I haven’t even touched on economics….

The part where Arakawa nails setting best, though, is in her portrayal of the farms themselves. I’m sure a lot of city people think of farmers as a kind of homogeneous lot. This assumption couldn’t be more untrue. Farming as a whole is really broad. There are a lot of different types of crops and animals, and what each farm raises depends on a lot of different factors. As a result, just like farmers often have similar perspectives and attitudes but wildly different personalities, farms are all run in unique ways. While they may raise the same crops or livestock, they’ll still all feel unique. They have personality and character of their own that reflect the people running it.

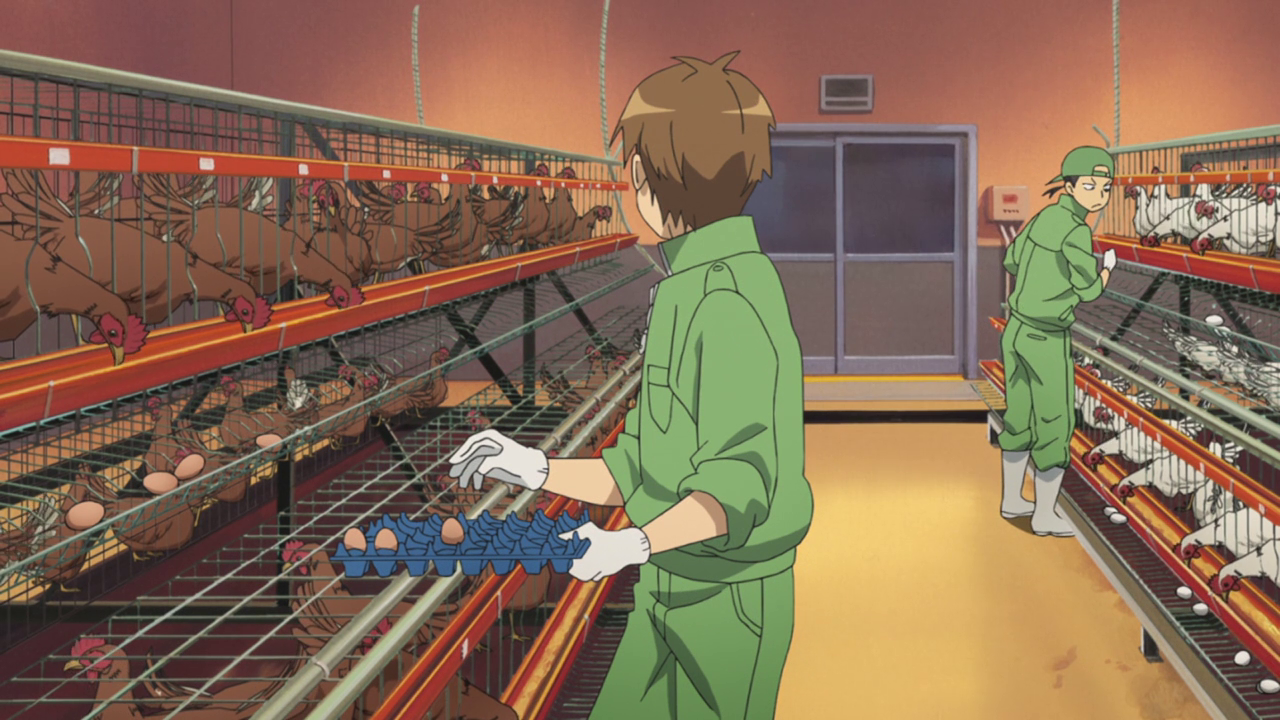

Compare the chicken coop seen in Silver Spoon to the one on the farm I stayed at. The former is designed with efficiency in mind, so eggs can be easily found and quickly gathered without interference from the chickens themselves, as well as allowing for the cages to be removed and the room to be repurposed if need be. The latter is a far less efficient system, requiring workers to search for eggs that may not have been laid in the roosts, but it’s also designed to be ecologically efficient, with the chickens living a more active style and a floor designed to both provide bedding and to break down manure so it doesn’t smell. And let me tell you, chickens can smell really, really foul (pun unintended).

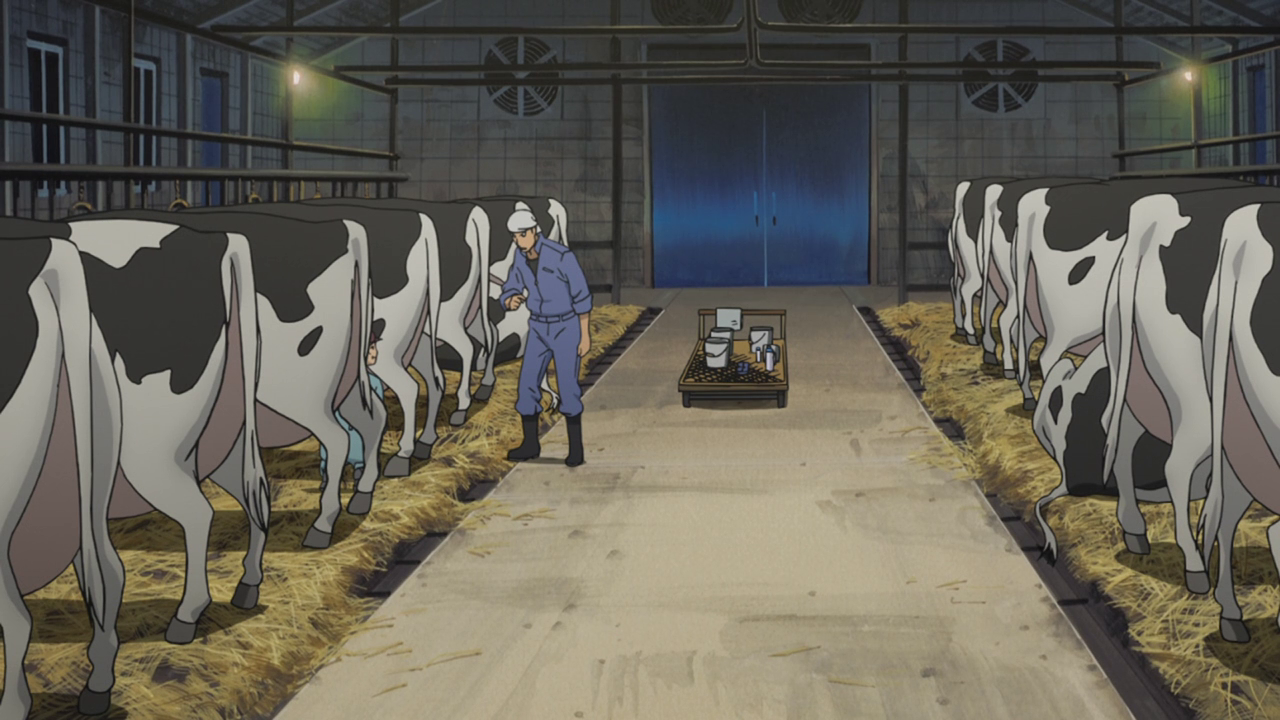

We’re also shown several different family farms partway through the first season, when Hachiken spends his break working at the Mikage farm. We see the Mikage farm, which is an average-sized family operation, the small Komaba farm, and Giga Farm, the giant operation that Tamako’s family runs.

At one point during his time with the Mikages, Hachiken also stumbles across the remains of an abandoned farm, one that presumably went out of business years ago.

Four very different farms, but four that all feel very real. My grandparents’ dairy farm was structured similarly to the Komabas’, and was likewise run by just a few people. There’s an abandoned farm or two within walking distance of my house. And while I personally don’t have much experience with setups that resemble the Mikages’ or Giga Farm’s, I’ve seen things that are at least similar.

By showing off all these different types of farms, Arakawa has painted a heterogeneous image of Silver Spoon’s setting–which ironically gives it more of a sense of place. Like people, the places in Silver Spoon are similar, but different, each with their own uniqueness and personality. We’re not just seeing one aspect of the setting, we’re getting an all-encompassing view. We’re being given the entire sense of place rather than just certain aspects of it. We’re not seeing the world through the eyes of students in school like in No-Rin. We’re not seeing it through the eyes of children just trying to have a good time like in Non Non Biyori. Instead, we’re seeing this through the eyes of a community as a whole, making it feel more complete and more real.

That’s not all there is to the setting, though. There are plenty of themes and ideas presented in the show that are vital to the setting. However, these themes will be getting their own post in the near future. Look forward to it!

1 comment / Add your comment below