Part 1: Zetsubou~, Zetsubou~, Zetsubou~

…So there was no hope after all. All those years, toiling away alone…. But well, now that I’ve failed…I feel so relaxed.

~Ishii, Chapter 16

Shoujo Shuumatsu Ryouko, localized as Girls’ Last Tour, is a series by Tsukumizu that focuses on Chito and Yuuri, two girls driving around a post-apocalyptic world in a Kettenkrad, continuously moving, scavenging for food, shelter, and fuel wherever they can find it. It’s a Sisyphean existence where nothing is gained or accomplished past being replenishing their reserves to keep moving. They have no purpose beyond continuing their own existence.

Most stories set in a post-apocalyptic, posthuman world would focus on the existential despair and dread of being alone in the world, without purpose, and constantly confronted with mortality. However, when Girls’ Last Tour delves into these ideas, it does so in a way that I can only describe as “existential joy.”

In episode 6 of the anime and chapters 14-16 of the manga, after Chito and Yuuri’s Kettenkrad has broken down, Yuuri cheerfully says that, instead of futilely trying to fix it, they should get along with the feeling of hopelessness. They then stumble across an engineer named Ishii, who’s testing the prototype for an airplane she’s been working on for years. As thanks for repairing their Kettenkrad, the girls help Ishii complete her airplane and watch its maiden voyage.

Ishii’s flight begins well enough, but her aircraft ends up not being able enough to withstand the flight, breaking apart in midair. While she manages to eject from the wreck and parachute down safely, she’s flown far enough that she’ll end up floating to a depleted lower stratum, left with nothing and unable to reach the abandoned air force base she called her home. However, as she floats down, she does not express dread, but relief. She’s been freed from the project she’s been tethered to for so long, and now that it’s over, she doesn’t have the desperation or self-imposed responsibility that’s been weighing her down. Whether the outcome was a success or failure doesn’t matter at this point, and there’s nothing that she can change about it. As Chiito and Yuuri watch her from afar, wondering why she’s smiling, Yuuri echoes her earlier words by suggesting that Ishii is getting along with the feeling of hopelessness.

Part 2: Ugoku, Ugoku

So with a 1, 2, 3 start walking

Today and tomorrow and yesterday are all the same

So with a 1, 2, 3, start walking

In the opposite direction the world is turning

~Lyrics from the opening theme, “Ugoku, Ugoku”

The idea of travel is vital to Girls’ Last Tour, so much so that the journey is what the “tour” in the title refers to and the anime’s theme song is titled “Ugoku, Ugoku” (approximately translating to Moving, Moving). As they remark at one point in the series, while it would be nice to settle down, staying in one place for a long period of time would deplete their food stores in no time. It’s an existence that is, as I mentioned before, Sisyphean.

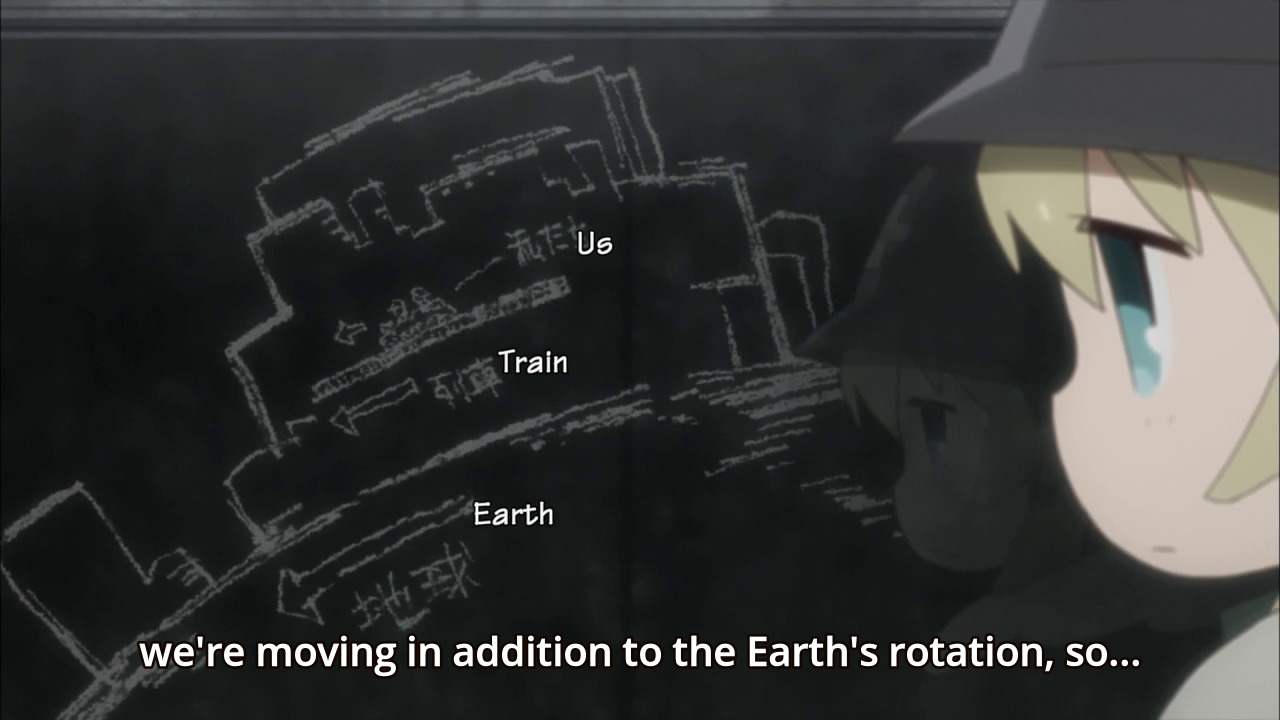

The series emphasizes this by using motifs with a cyclic nature that show movement, but no clear destination. When the girls drive their Kettenkrad while on a train, Yuuri remarks that since they’re moving in a train that’s also moving, they’re going even faster than usual. Chito corrects her, attempting to explain relative speed with her limited knowledge, explaining that the world itself is constantly rotating at high speed, so they’re always moving extremely fast whether or not they themselves are actually moving.

What’s more, Chito isn’t certain whether they’re moving with the Earth’s rotation or against it, but it ultimately doesn’t matter since it doesn’t affect their speed anyway. The Earth’s very rotation is, like their own, movement that’s necessary for life to exist but ultimately accomplishes nothing.

The idea is even more strongly present in “Spirals,” chapter 21 of the manga and in episode 8 of the anime. It details Chito and Yuuri traveling to a higher stratum by taking a spiral ramp on the outside of a tall building. While the spiral can be used as a metaphor for constant progression (e.g., Gurren Lagann), Girls’ Last Tour uses it to show the tedious, cyclic nature of constant movement. They go around and around so many times that it becomes dizzying and they start to lose track of whether they’re even traveling up or down.

Ironically, the constant repetitive movement makes them miss the unchanging nature of their usual life when repeating an endless, unchanging cycle of travel and resupplying is quite similar to the idea of traveling in circles over and over.

This segment also ties into an idea ever-present but lurking below the surface of Girls’ Last Tour: just as Chito and Yuuri eventually manage to make it to the next stratum and exit the spiral, their cyclic journey will eventually have an end–the same inevitable end all things have.

In episode 9 and chapters 22-24, Chito and Yuuri explore a broken down facility where they ponder what exactly being alive means. In interacting with an intelligent robot and learning some about the city’s infrastructure and the world’s current ecosystem, they come to the conclusion that maybe “life” is something that has an end. In the following afterward, mangaka Tsukumizu reflects on how the idea of something going on eternally makes her feel easy and lonely. She writes “Life, civilization, the universe–I’d like all of these things to be over at some point. I think that having an end is a very comforting thing.” Once again, rather than focusing on the despair that may accompany the idea of an ending, the series instead gets along with the feeling of hopelessness.

Part 3: Sometimes Nice Things Happen

“Even if it’s meaningless…sometimes, nice things happen.”

“Even in a world like this?”

“I think so. I mean, look how beautiful the view is.”

~Yuuri and Kanazawa, Chapter 8

The idea of getting along with the feeling of hopelessness is why Girls’ Last Tour is ultimately able to feel so uplifting. Living in a post-apocalyptic world where other humans are rare and every day is a struggle to survive would drive anyone through the five stages of grief. However, this series takes place long after the characters have gone through these stages and landed on the fifth and final one: acceptance. It’s a world where everyone has been confronted with and forced to face their own mortality, and as a result, they’ve long since come to peace with it. Since they’re getting along with the feeling of hopelessness, it is no longer able to interfere with and dampen the feeling of hope for them.

This manifests within the series as Chito and Yuuri finding reason to continue their hopeless existence by discovering joy and beauty in the small things in life. They consistently turn their hardships into something positive by focusing on what makes them happy rather than worrying. For example, nearly freezing to death in a snowstorm is followed by the first hot bath they’ve had in a long time, and being forced to take shelter in the rain results in them appreciating the noise of droplets of rain rhythmically striking metal.

In Episode 3 of the anime and chapters 6-8 of the manga. Chito and Yuuri encounter a man named Kanazawa, who has dedicated his life to mapmaking. They spend a brief time traveling with him, during which an accident causes him to lose all his maps–and with them, his will to live. He is forced to confront a world that has robbed him of his purpose. Afterwards, Yuuri attempts to pull him from his despair, telling him that “sometimes nice things happen.” She urges him to look out over the city, where the automated lights have just come on, causing the world below them to look like a field of stars.

This is the simple philosophy through which the series is able to reconcile hope and hopelessness: sometimes nice things happen. That’s it. In a tedious, hopeless world, sometimes that on its own is reason enough to live.

This interplay between joy and despair is on full display in the final episode of the anime. When Chito and Yuuri end up in a facility that connects their camera to an image display, they end up looking through all the photos and videos that have been saved on it over the years, dating back at least as far as the collapse of civilization. They see a variety of both joyful and tragic events interspersed with each other–new births, school festivals, funerals, sporting events, heated political debates, announcements of war, jumping dolphins, military shootings in the streets, idol festivals, large-scale destruction…all juxtaposed together, giving equal weight to all these events, all underscored by Chopin’s Nocturne Op. 9 No. 2.

Life, death, joy, tragedy, personal events, global events, fun, sorrow…all are put on display. We see that sometimes nice things happen, even in a world like the one in Girls’ Last Tour. And perhaps tragedy makes these nice things even nicer. Maybe embracing the hard things in life gives us the freedom to appreciate the good things. Maybe endings themselves aren’t something to dread, but something to embrace.

Maybe, just maybe, we can experience joy through getting along with the feeling of hopelessness.

Translations used in this post are taken from both Yen Press’s translation of the manga by Amanda Haley and Amazon’s translation of the anime (translator(s) unknown).

Reblogged this on eff-fumes domain.